Lili Almong's photographs tell the story of the women of today’s China through their domestic and work environments. Her series focuses on minority women, some of whom have only recently been exposed to modernity.

My past work on women and their private lives inspired me to explore a fascinating topic: women in today’s China. I wanted to look at the paradox of China as a society in extraordinary transition and yet still deeply embedded in tradition and I wanted to see how the communist revolution, with its vision of the nobility of physical labor and emphasis on gender equality, left its mark on women's and personal identity in a changing China.

Islam reached China in 651 C.E., just 19 years after the death of Muhammad, when a maternal uncle of the Prophet was sent as envoy to the Tang emperor Gaozong. Over the next 1,400 years, the fortunes of the religion varied widely, although it never became a principal faith of the 92-percent majority Han people. With the Communist victory in 1949, Islam was disparaged, like all other religions, by Maoist who viewed it as part of the pernicious “olds” (old ideas, old culture, old customs, old habits) to be eradicated to make way for the secular, enlightened future. Freedom of religion did not return officially until 1978, under Mao’s economically liberal successor, Deng Xiaoping. At present, Islam is practiced by about 27 million people, 2 percent of China’s population, mostly from ethnic minorities.

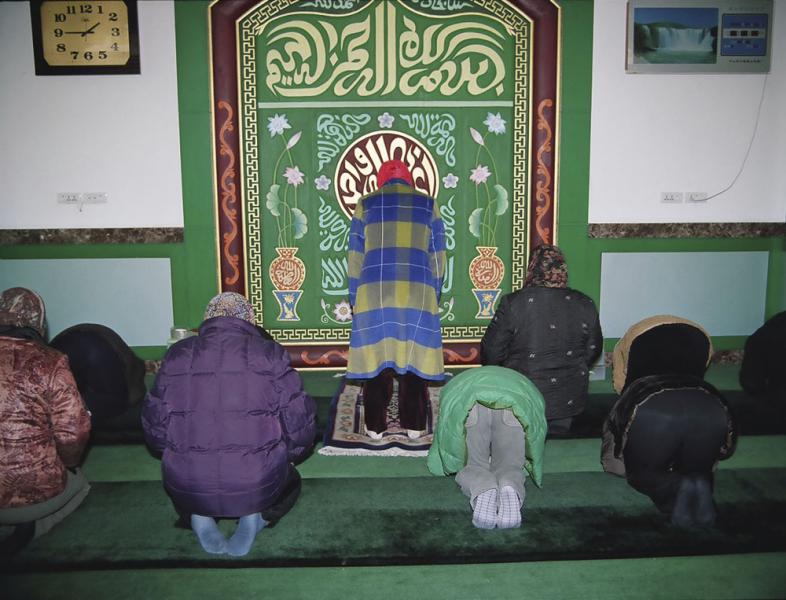

Along the way, however, a unique development took place. Beginning in the 16th century, Muslim women in central China began to establish their own mosques—a practice largely unknown in global Islam, which either segregates women during communal worship. More astonishing still, female imams—again an aberration from tradition—arose in a number of Chinese locales, where the tradition continues to this day. In the province of Ningxia, the heartland of Islam in China, Muslim women pray and celebrate together, and female imams teach other women the Quran. Women’s mosques are independent and autonomous from male-run mosques.

The explanation for this cultural peculiarity seems to lie in geographical isolation and strong indigenous customs. Muslim practitioners in central China probably had more intense contact with the Han majority around them than with their Islamic brethren abroad. And within the patriarchal framework endorsed by Confucianism, women—although relegated to a secondary status—bore many familial responsibilities, including the physical and spiritual welfare of their own gender. Moreover, the country’s prevalent faiths, Buddhism and Taoism, both provided the model of officially sanctioned nuns, who made religion their fulltime vocation.

The Muslim women depicted in the yards of their homes or mosques are primarily from the Hui group, which totals some 9 million people. While their heads are devoutly covered, the wide variety of scarves used bespeaks a social diversity—and sometimes a personal stylishness—at odds with clichéd notions of religious uniformity and austerity. Indeed, their head wraps become a metaphor for the imaginativeness with which women have long adapted to, redirected, and sometimes subverted all manner of putatively “defining” restrictions.

My photographs tell the story of the women of today’s China and their individualism in their domestic and work environment. They also focus on minority women, some of whom have only recently been exposed to modernity. They also tell the story of the everyday lives of religious women with an emphasis on the extraordinary situation of Muslim women in China.

On my first trip to China in December 2006, I visited twelve women-only mosques in Shaanxi, Henan and Yunnan, and one private home in the Islamic quarter of Xian. In both group and solitary moments, Chinese Islamic women are passionately traditional, yet firmly enmeshed in modern society. Their religious and domestic expressions have resulted in images that are vibrant and colorful and also profoundly moving.