Samina Ali: You’re one of the few American correspondents the Iranian authorities permitted to work continuously in Iran throughout the 2000s. Why do you think you were allowed to report from there when others were not?

Azadeh Moaveni: I started reporting in Iran in 1999 during the reform era, when the regime was experimenting in loosening up. There was a slightly wider space for debate and the officials in charge understood there was some merit in projecting a more tolerant and less cliche image of Iran to the world. Journalists of Iranian heritage like me, who were reporting for the Western press, offered a safe way of doing that: we had deep personal incentive to report more truthfully on Iran, but also, because we carried Iranian passports, were easier to monitor and if necessary pressure or intimidate.

The authorities who monitored us might have found us bizarre (we had gender mixed dinner parties, etc), but they knew we weren’t spies or out to topple the regime. There were many, I believe, who actually respected our work.

Can you briefly describe what sorts of changes you’ve seen there over the past decade?

I first landed in Iran as a reporter in 1999, and can scarcely compare the Iran of that era to today. Well, it’s actually quite comparable in terms of repression, human rights abuses, etc. But Iranians themselves are strikingly transformed. The events of that past decade, the failed experiment in reform, the crackdown of 2009, has led to a profound self-awareness, about the necessity of change, the need for accountable government, the unanimous desire for better quality of life and opportunity. How to bring that all about peacefully is now the question.

I had the opportunity to interview Dr. Shirin Ebadi for the exhibition with whom you co-write Iran Awakening. In our interview, she told me that Iran has one of the strongest feminist movements in the Middle East. Do you also find this to be true? And what do you think it is about Iran that contributes to this?

This is absolutely true, though the flip side is that the movement is cowed and not permitted any space to operate meaningfully. Its leaders are exiled or in prison, and those still on the ground are far more inhibited than they were, say, a decade ago. But women are still pushing the boundaries in their various fields, they are pushing for space within the limitations. Dress is a great example of this, in the last thirty years Iranian women have managed to reject the black chador as mandatory dress, and have taken ownership of the manteau, a lighter, sometimes shorter coat, as an alternative. There is a burgeoning fashion scene around this manteau, and all that reflects women’s insistence on expressing their individuality, on demanding their rights as citizens to choose -- within the limitations -- what they put on their bodies.

The roots of this are social-cultural, also demographic. If you look at numbers and compare regionally, Iranian women are fairly well-educated and literate, and tend to work outside the home more and have greater access to global culture than women in neighboring countries. They also inherit a long tradition of engagement with culture, arts, and politics, and their physical presence in public life is taken for granted by mainstream society.

Realistically, what kinds of changes do you think this movement will bring about?

It’s hard to measure, and of course all the regressive and discriminatory laws are still in effect, promoting women’s inequality and domestic violence, and more recently even limiting women’s access to higher education. But women’s resilience, perhaps not as a movement but as individual actors, has been hugely successful in creating change on the ground, in families, through daily life, at the level of perception. When women work more outside the home, they demand more say inside the home, and that is changing gender dynamics within households. When women push back against conservative Islamic dress, that puts a giant hand up to the state, telling it effectively that it can only push so far. When women fill up universities and gain reproductive rights and have less children, they are carving out a freer, more autonomous space for themselves in social sphere. All this is outside politics, effectively, but still transforming.

How was Iran affected by the Arab Springs, if at all?

Let’s not forget Iran’s 2009 summer uprising preceded the Arab Spring! For a while the Arab protest movements commanded Iranians’ attention, and you would hear slogans at demonstrations in Iran where people allied themselves with countries like Egypt and Tunisia. But it hasn’t kicked off anything in Iran, for various reasons. The opposition in Iran is under house arrest, its leaders are fractured amongst themselves and not at all universally popular, there’s no agreements as to either means or ends. People’s quality of life is being devastated by sanctions, and the government has refined the art of crushing any street protest.

Your book, Lipstick Jihad, takes readers into a part of Iran that outsiders rarely glimpse. What inspired you to write this book?

I was sick of the single narrative about Iran that ruled in the West, and the limitations the news story posed in trying to challenge this. I was phenomenally inspired by the young generation I encountered in Iran, they were my inspiration, and I wanted to tell their story -- their originality and creativity in the face of censorship, their courage and resilience in the face of repression. I needed a book to tell that story, as a medium it permitted the storytelling I needed to create that alternative narrative.

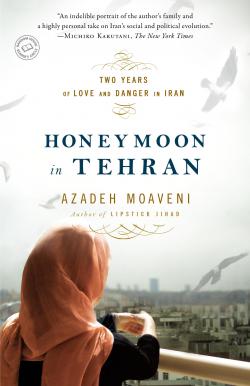

The book following that, Honeymoon in Tehran, is an intimate look at your personal life and how you met and married your husband. As a reporter, was it difficult to turn the lens onto yourself – to make your personal life the topic of a story?

Actually, yes, I found it excruciating. There is far more of the shame culture inside each one of us than we realize, and this is something I had to confront in myself. The taboos against writing about sexuality and family are extraordinarily strong, and the temptation to self-censor, as a result, is great. So the writing of Honeymoon in Tehran was painful for me, though instructive.

I tried to remind myself there was a point to it all. Memoir is a powerful way to engage with a far wider audience than conventional, narrative non-fiction. But I’m a fairly private person, I even find Facebook somewhat difficult. I enjoy first-person, essayistic journalism, I find that being an honest presence in the story is often truer to what journalism involves and asks of us.

In the U.S., many writers are concerned about the future of publishing. What is your advice to aspiring writers? Is there a future left in writing books?

As long as there are people, there will be an audience for stories. What’s happening in publishing is worrisome, but the changes are also opening up new possibilities and opportunities that didn’t exist a decade ago. The option of self-publishing a single short story on Amazon, for example, or a piece of magazine style journalism is very exciting. Young writers can experiment in any form they choose, as there is now a platform for virtually everything.

What worries me more is the future of journalism, particularly in the United States. Mainstream media no longer has the budget or infrastructure for the kind of investigative and international reporting that is vital to a democracy. At some point, the US will need to reconsider its whole media landscape, and think about a public-private partnership similar to what Britain has with the BBC.

The media has created so many stereotypes of Muslim women. You work in the very media that can sometimes be the problem. How do you negotiate this irony?

Ah, this is a great struggle. When I was a young foreign correspondent, it used to make me hyperventilate in hotel lobbies. The stereotypes of Muslims in general, of Iranians and Palestinians, as violent people without aspirations or culture. And this as operative in book publishing as the media, so I confront it in every field of writing.

I’ve found relying on and talking about the concept of narratives very helpful, the simple fact that we all have different truths, different perceptions of even a basic chain of historical events. Nations and societies trade in narratives, as do media companies and publishers. There are great incentives and temptations to only understand and acknowledge one view, one interpretation of events or history. I say this all the time these days, if I’m talking about Ahmadinejad in an interview or the film Argo or whatever else.

But Muslim and Eastern societies also stereotype and caricature Western women, it goes both ways. As with any dysfunction, just naming it all the time and being aware is helpful, a step in itself.

We’re ten years beyond 9/11. Do you think people are more open now to hearing the realities of Muslim women’s lives?

I’m often in the midst of the fray, and live in a country where Muslims are either demonized or treated too daintily by the media, so I find it hard to say. I don’t think Western feminists are any closer to engaging with Muslim women in a productive way; the arguments seem as polarized and deaf to me as a decade ago.

I spent the first half of my career totally engaged with this question, how to get the West to understand us better, how to convey our reality, how to prove that we were not all chained to the stove frying onions. I would lay awake at night thinking about Sally Field, and how much I hated her for Not Without My Daughter. Sally Field, for god’s sake, what a banal thing to be fixated on! That indignation fueled me for many years, but it also kept my attention too honed on the West, too stuck in the role of explainer or polemicist, holding up the alternative reality.

Now my focus has pivoted entirely, I’m much more interested in having dialogue with and trying to bring about some change within my own community, within the Iranian diaspora and Iranians inside Iran. This is where my real passion is these days, to engage with Iranians about our own cultural and social issues.

Final thoughts? What are you up to lately?

Fiction! I’m all about fiction these days. It offers such a wider space to explore complicated, painful truths that are sometimes just too raw or layered to confront directly. The novel doesn’t aspire, like journalism, to be a first draft of history, but it can often end up being a vivid portrait of a society.

I’ve just read a superb novel by Elif Shafak called Honour, and have come to understand the phenomenon of honor killing in a whole new way. She had me sympathizing with the killer in her tale as much as the victim, and spun this incredibly rich tapestry of accountability.

- Log in to post comments