In this exclusive interview, Muslima curator Samina Ali sits down with Palestinian artist Laila Shawa to discuss her long career, the veil, and her hopes for the future of Palestine.

You have quite an impressive background: born in Gaza to wealthy parents, you studied first at a boarding school in Cairo then trained seriously in art at the Leonardo Da Vinci School of Art. Did you know at an early age that you wanted to be an artist?

I had a great curiosity about art at a very early age. I could not say if I was that aware of wanting to become an artist. I simply had an instinct for what I considered beautiful. I drew quite well, but that was the end of it. After graduating I joined the American University in Cairo (AUC) to study political science and sociology, more or less following into the footsteps of my family. I was aware that it did not satisfy me! One afternoon, I was having tea with my father and his friend, an architect who was Italian/ Egyptian. In the course of conversation my Father asked me how I was faring at university, and my response was, “Not too thrilled!” My father‘s friend then asked what I was reading at University, and I told him. He looked very puzzled and asked me why, since I drew very well, did I not choose art? I looked at him in total amazement and asked where would I go for that? He responded by telling me that he taught at the Leonardo Da Vinci art school, and that he could get me in. That was it! I looked at my father for a response, and he just shook his head and said “What a brilliant idea!” The rest is history. But it was pure coincidence that changed my life!

I’ve heard your work described as being intensely engaged with the physical aspect of production, moving with ease across media from print to oil on canvass to, more recently, installation. Can you briefly speak to your process and your use of these various types of production? Is there a link between what you’re painting and the material you use?

I was trained mainly as a painter, later as a photographer, but as we evolve as artists—we discover that one tool of the trade does not fulfill all requirements.

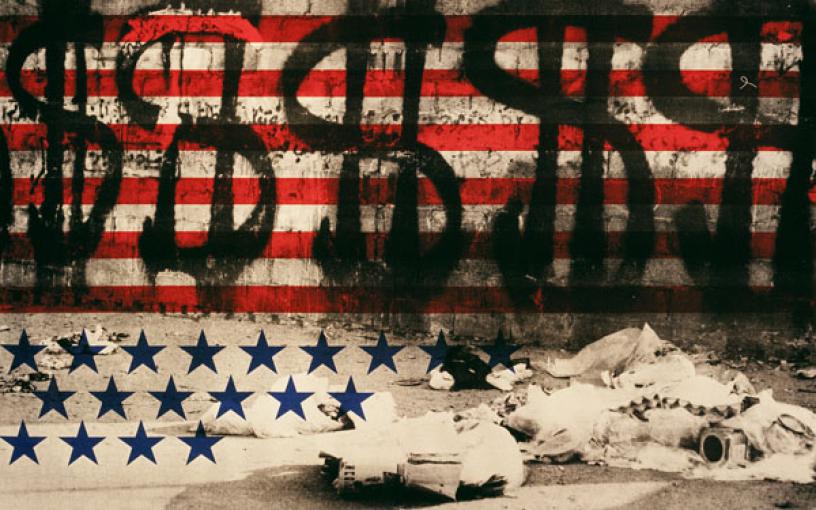

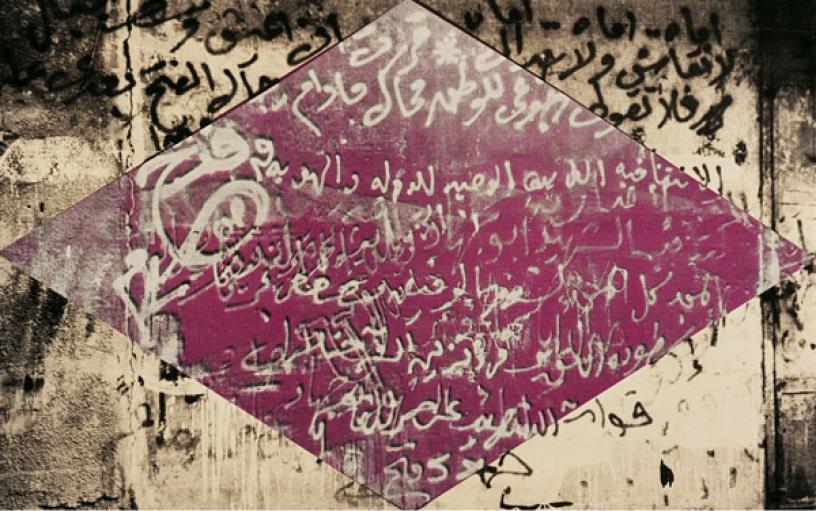

I found myself facing subjects, such as graffiti on walls, and the only medium I could use was photography, which also led me to printing. Later on, as in the case of installations, the subjects dictated the use of mediums. With the existence of so many mediums, artists adopt different techniques in their work. It is a matter of necessity and evolution.

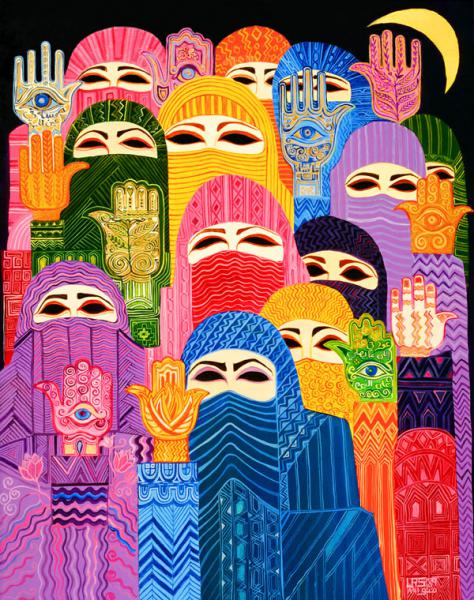

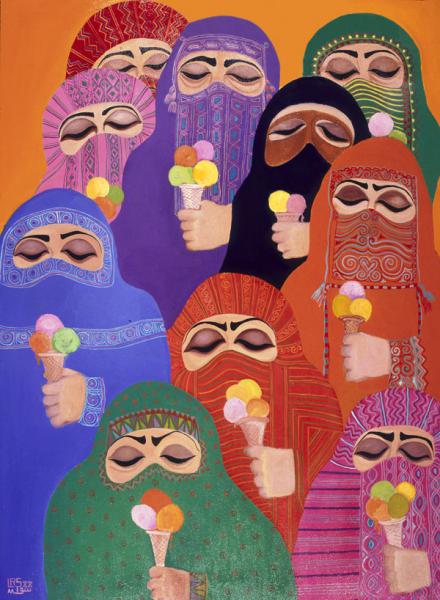

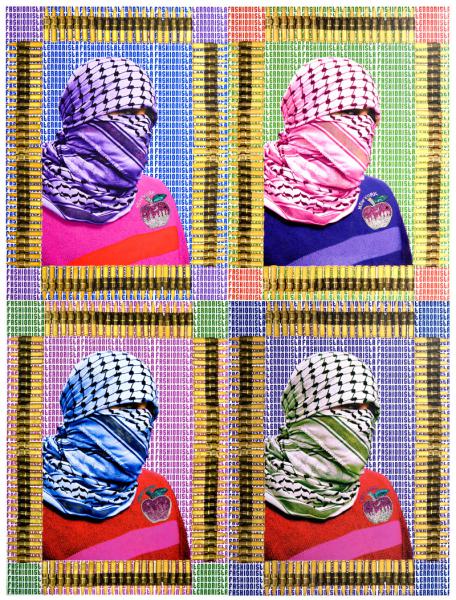

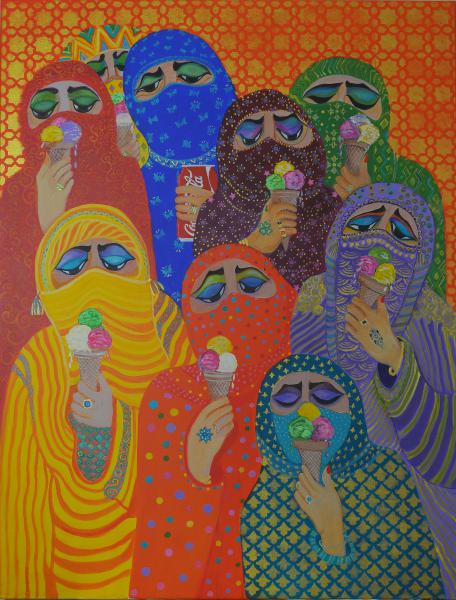

In 1987, when you moved to London, you began a critique of the veil. The Impossible Dream, for instance, depicts a group of women holding ice cream cones in front of their veiled faces. It’s a humorous, catch-22 moment. What were you hoping to convey about the veil?

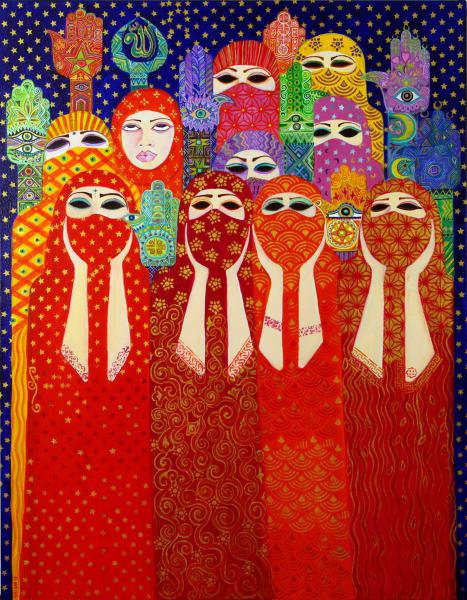

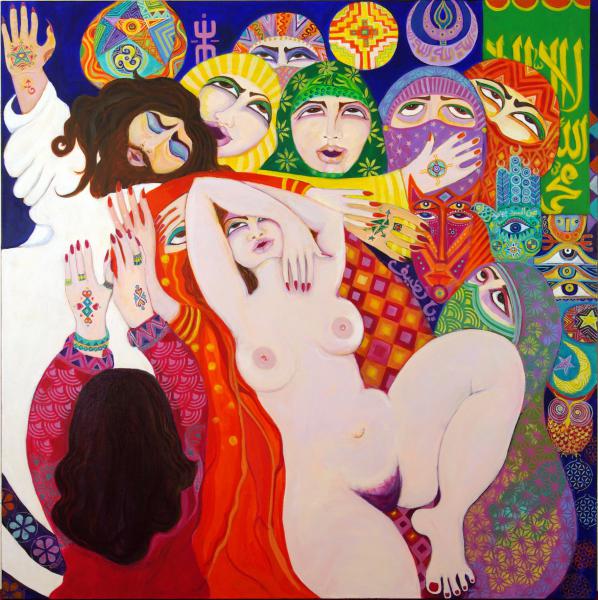

The veil is what I would term as a Bidaa--something which was introduced to Islam (possibly by the Byzantines in the late 7th Century), but has nothing to do with the teachings of Islam. The resurgence of the veil, starting with the Islamic revolution in Iran and its spread into the Middle East, was more of a sociopolitical phenomenon designed to control and subdue women, the so-called weaker sex, as a result of men losing control of their lives due to Western hegemony and complicit and corrupt dictatorships, in their various forms.

An incident in Gaza triggered this series of works. In the case of the Palestinians, women played a phenomenal role during the first Intifada. They stood up to Israeli soldiers while their husbands were hiding in fear of losing their jobs, as many of them worked in Israel as daily cheap labor. Their children were throwing stones at the IDF. The women defended their children and their husbands, which resulted in men losing their positions as heads of family. Women became too powerful and had to be put in their place. Hence the veiling of women, at least in Gaza—but I am sure the same applies to the rest of the Islamic World, although the reason may vary.

I come from a long line of strong women. My grandmothers were very powerful; my mother was a follower of Simon De Beauvoir. I grew up as an equal, and always believed in the power (and to some extent the supremacy) of women. Watching women subdued—but above all, seeing women accept it—is something I could not accept. My critique is more of the women themselves—their complicity in reducing their status to an invisible state, while at the same time yearning silently for the freedom Western women seem to enjoy. The tug is between the two states. So the message is obviously that they should give themselves more value and certainly more respect.

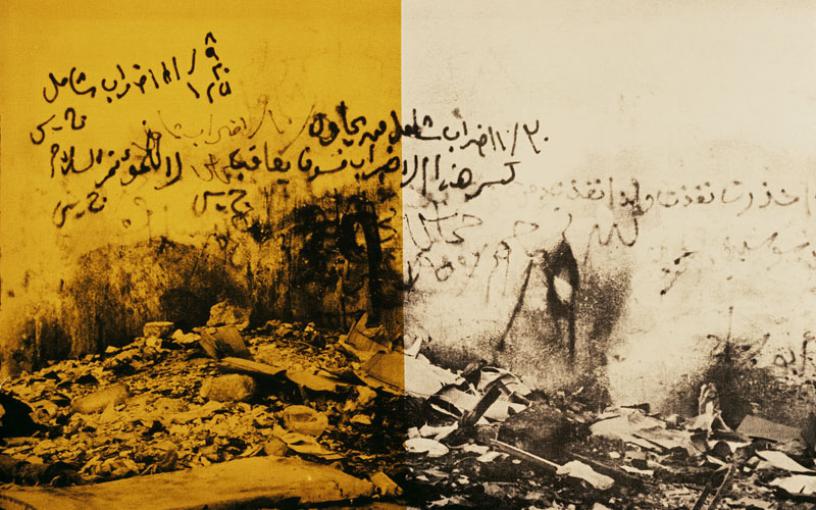

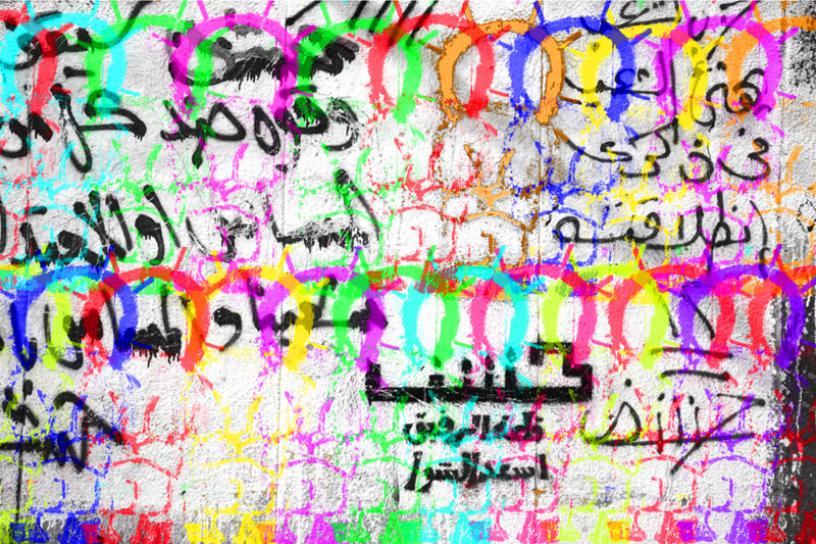

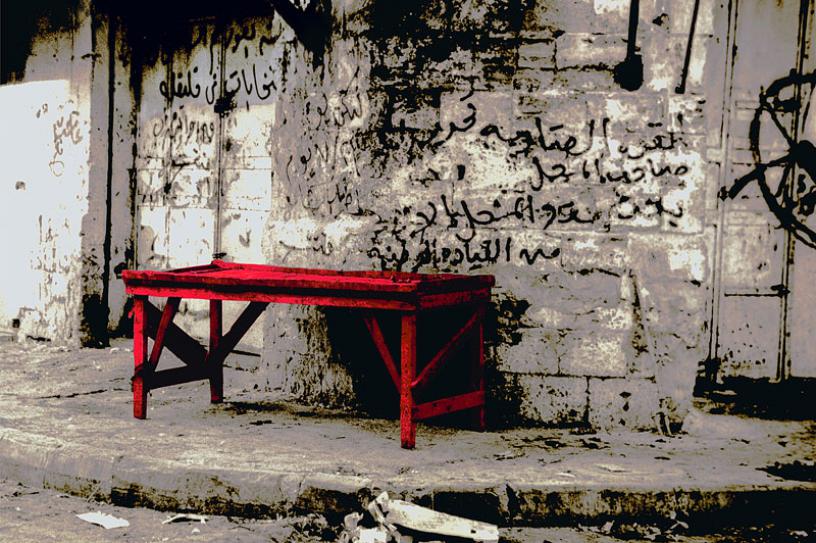

I want to speak about The Walls of Gaza, which was inspired by photographs taken of graffiti appearing on the houses of Gaza during the first Intifada. The writing carries anything from personal communications to political slogans. In Gaza specifically, what does graffiti art represent?

I believe the Gaza Graffiti differs completely from urban graffiti that one sees in big cities around the world. In Gaza, graffiti on the wall was the only method available to Palestinians to communicate with each other. The Israeli occupiers banned any form of media in Gaza, such as newspapers, radio, or television. The writing is cursive, spontaneous and hurried. It changed almost daily to update whatever was happening in Gaza.

Children of War, Children of Peace is a moving series illustrating the presence of a traumatized generation of children. If Israel and Palestine are ever to reach a peaceful solution, what do you think it will take?

This is a very complicated issue, but for peace to be achieved between Palestinians and Israelis, it would take a complete change in the manner Palestinians have dealt with the issues of resistance and negotiations. We need a much more enlightened leadership that is not controlled by the West. The biggest problem I can foresee is the existence of a traumatized generation of Palestinians, which may present very serious problems to a stable Palestine, should this ever be achieved.

When you look back on the Israeli-Palestinian history, what one lesson do you want to relay to our international community, especially the younger generations?

I think my advice would be for any new generation is to read history from the correct point of view. The problem with the Palestinian issue is that it is discussed from the middle of the story, while ignoring totally the origins of the conflict. Most people don’t know the real history of what happened in Palestine. History is written by the victors and the truth is distorted. The information is there for those who care to find it.

You are an internationally recognized artist whose work graces major public and private collections around the world. Of your many accomplishments, what is the one you’re most proud of?

It would not be a painting, but a building I helped design and build in Gaza. It took 12 years of my life, my father’s life, and my ex-husbands life to build a cultural center in Gaza that carries the name of my father. It was confiscated by Arafat when he arrived in Gaza, it was bombed by the Israelis, and today it is controlled by Hamas, and not serving the purpose it was built for—to connect Gaza culturally, with the outside world.

The Centre was designed to have several exhibition spaces, three auditoriums that open up to become one space, a theatre for performance arts, a public library, and a printing press. The next stage (which I insisted on, but never achieved) was an art museum, to house the work of contemporary Palestinian artists, and an art college attached to it. We were hoping to invite artists from all over the world to exhibit and perform. It took 12 years to build , due to the hurdles created by the Israelis, during which my husband and I abandoned our real work in the outside world, and focused on the building—a massive price to pay, in view of the results. But we were so full of hope and so confident of the future. Our great and misplaced optimism vanished of course later on!

I still hope that one day I will be able to go back and restore the building to its original purpose.