Jessica Pabón interviews blogger Soraya Morayef, who documents graffiti street art in Egypt. Morayef explains how the proliferation of street art was inspired by the revolution, how it communicates to the masses better than language, and what the particulars of being a woman painting street art might be.

Since the beginning of time humans have been writing on walls in a number of ways—using mud, blood, pigments, and various tools to draw, carve, and paint symbols and alphabets. The form and classification of the graffiti itself changes by location, by writer/artist/activist, and by time period, but from the Ancient Egyptians’ sophisticated hieroglyphics to the stenciled and pasted street art of modern day Cairo the function remains the same—graffiti is used to communicate. We graffiti to express ourselves; to tell a story, to mark a territory, and ultimately, to call out for some kind of recognition. Graffiti elicits a response by design, literally and figuratively.

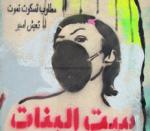

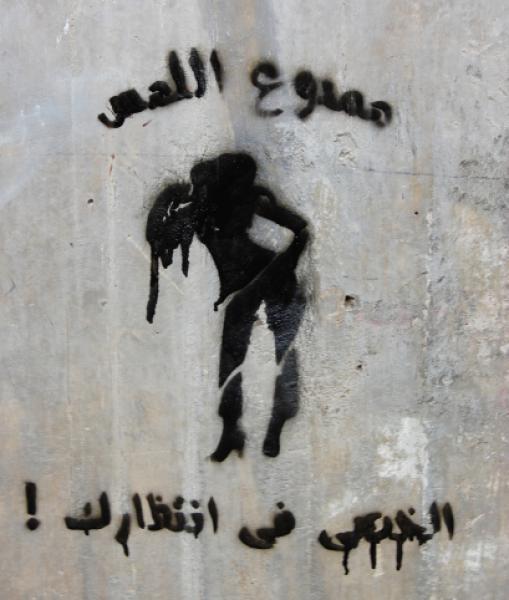

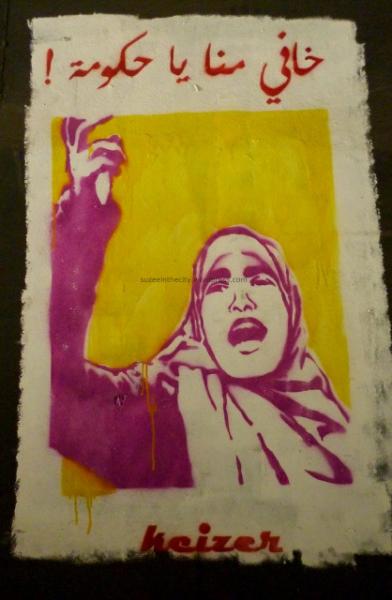

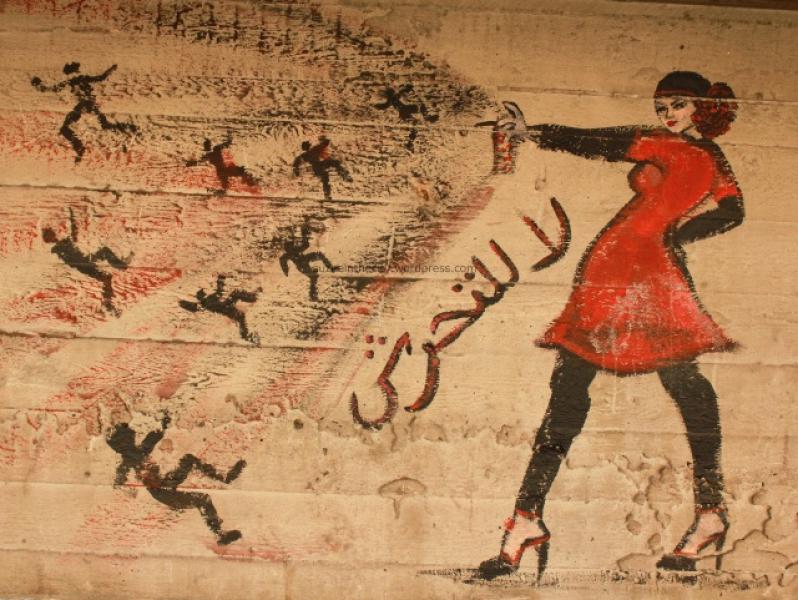

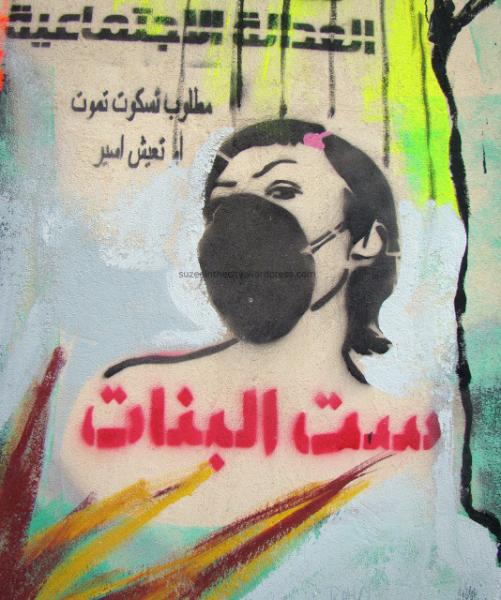

In a world that has historically and consistently limited the expression and development of women and girls under innumerable manifestations of heterosexual patriarchal rule, the value of a mostly anonymous, visual, public, and ephemeral art form cannot be overstated. Muslima is an exhibition dedicated to demonstrating how contemporary Muslim women use artistic practices and critical discourse to define themselves against limited and static stereotypes. Street art is one such practice. Contemporary street art is a performative act through which women and girls communicate something beyond their limitations—to inscribe their opinions, express their emotions, and demand their agency.

In December 2012, cognizant of my research with women in Hip Hop graffiti subculture, a colleague sent me a blog post she had come across on suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com. Dated January 7, 2013, “Women in Graffiti: A Tribute to the Women of Egypt” begins:

Since January 25 [2011], so many foreign reporters have waxed on about the awakening of Arab women in the Arab Spring; and how the revolutions liberated us/made us wake up and smell the coffee/made us throw off our headscarves and run happily through the meadows. This, in my opinion, is crap.

SuzeeintheCity’s direct and sarcastic tone caught my attention in an instant. It IS crap, I thought to myself. In that post, arguing that women did not experience an “awakening” because of the revolution but rather as part of their well-established struggles, she listed artists I had never heard of such as: Aya Tarek, Hend Kheera, Hanaa El Degham, Bahia Shehab, Laila Magued, Mira Shihadeh and the collective NooNeswa. She gave them the kudos they deserved at activists and artists, as equal participants in Egypt’s street art culture.

Since June 2011, SuzeeintheCity has been closely documenting (through photographs, interviews, and textual analysis) how the January 25th, 2011 revolution in Cairo, Egypt has inspired a distinct proliferation in the production of street art. Despite the fact that there is no law against graffiti per se—there are laws regulating the destruction of property (public and private) that come with monetary consequences (50 £; roughly $7) and perhaps “community service” (painting the wall white)—in her earliest posts, she noted that Cairo’s street art was usually found in hidden places and erased in record time. Cairo’s street art is no longer sporadic, or concealed, it is prevalent. In February 2012, she wrote:

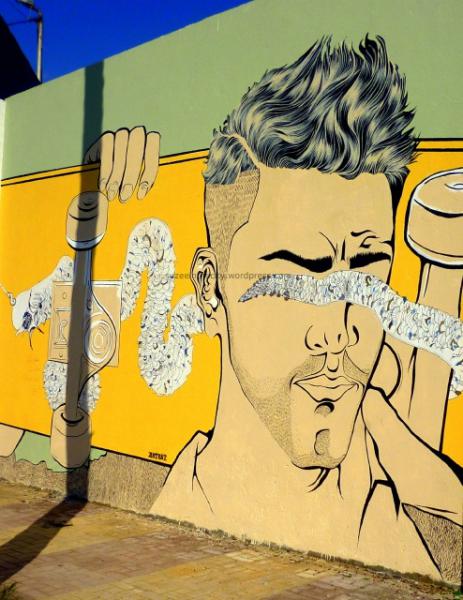

Graffiti has spread like wildfire throughout Cairo in the past 12 months and is used by young Egyptian activists to commemorate the victims of the uprising, and to raise awareness of political injustices and crimes committed by the Egyptian military. In the face of the mainstream media’s campaign to tarnish protesters as criminals and cover up military crimes, many activists have turned to graffiti as an alternative means of reaching the average Egyptian on the streets.

With over 100,000 hits, it seems SuzeeintheCity isn’t the only person interested in the relationship between the art and audience, the messages, the social context, the Western aesthetic influences (i.e. British artists such as Banksy, and North American pop culture icons). She explores the alterations particular to “#NewEgypt” sensibilities, the aesthetic of repetition with difference, censorship and the politics of erasure, “symbolic solidarity” between Arab nations, risks and consequences, corporate graffiti-styled advertising campaigns, and the gallery vs the street. SuzeeintheCity has dedicated herself to documenting each revival of protest and uprisings paralleled by the resurgences in visual commentary.

The background image of the SuzeeintheCity blog features an aerosol-paint can and text that reads, “Wipe it off and I will paint again.” SuzeeintheCity told me that “the authorities don’t quite know how to deal with [graffiti artists] because every time a wall is defaced, a wall is painted clean; graffiti returns in many layers and even more aggressive than before.” The message is clear and more than a metaphor. The “adamant, resilient, and determined” activists/artists of the opposition refuse to be silenced in the face of the governments’ increased policing on street art…on freedom, on the people’s voices, and on the revolution.

Curious about what SuzeeintheCity had to say, I conducted an email interview with her. The text that follows is a transcription of that interview.

Jessica: Can you tell me a bit about yourself? How did you get interested in street art in Cairo?

SuzeeintheCity: I’m a 30-year-old freelance journalist/writer. I am currently doing my Master’s in Creative and Cultural Industries at Kings College in London. I’m Egyptian; I’ve lived my whole life in Egypt. I graduated from the American University in Cairo.

I’ve always had an interest in graffiti. I enjoy traveling and every time I’ve traveled around the world I've seen a lot of street art and have always been a bit envious of the different graffiti scenes in different countries and wished that we’d had the same kind of scene back home in Egypt, but under Mubarak that was completely impossible. When you live under a police state of constant oppression and fear it’s only natural that the walls are completely bare and if there’s any art it’s government sanctioned and sponsored; the visuals that the government wants you to see, so patriotism, religion, support for the ruling National Democratic Party, support for Mubarak and his family. It’s very sanitized and very controlled, and when graffiti started emerging with the revolution and continued to spread throughout Cairo, as well as Alexandria as well as many other cities in Egypt, I became compelled to go down and photograph. It started with my own neighborhood in Zamalek. I noticed how everyday there’d be a new piece and the same piece would be removed within hours or days. So I felt not only an interest in taking the photographs, but also a need to document it because there was beautiful art that was being made and almost immediately removed.

I wasn’t aware of other people doing the same thing because it was still very early on in the revolution. I think I started taking photographs in April 2011, and I started my blog in May 2011, something like that. As I continued to blog, I got in contact with artists, some through common friends, some artists were already friends of mine, and some through social media. Through Twitter and my blog where they would reach out or their friends would reach out to me, so I would credit their work to their names. This is when I began to realize that I was actually doing a service instead of it just being a selfish hobby of mine. And later on I've understood that it’s a very good relationship between a graffiti photographer and a graffiti artist where there’s mutual respect and understanding that both parties have the common passion and the graffiti photographer is giving the credit where it’s due and the recognition where it’s due to the artists. And the artists, through the graffiti photographer, get documentation of their work—sometimes they won’t have time to go back and photograph it, or they’re working under pressure in a rush in risky situations.

Why do you think street art in Cairo is important?

Street art provides a narrative for Egypt’s recent history. It provides a narrative for pro-revolutionary society members, as well as activists, the families of martyrs, the faces of martyrs—visuals are always a lot stronger to disseminate information than text especially when you’re in a country where almost half of the population is illiterate. As far as I can remember I think it was 40%, but I’d have to check the statistics. Visuals are powerful and compelling and provocative and the fact that so many street artists have experienced people attacking them verbally and physically while they’re making art, or approaching them and offering to contribute financially or to help them in painting, or wanting to understand what the meaning is of the work that they’re making—this means that it’s provocative enough to compel a public reaction. And in that sense, street art is incredibly powerful. And I think that the interest shown by international academics, diplomats, artists, documentary makers, journalists, and whatnot—as well as, increasingly, the local society—shows that people have begun to pick up on the fact that if you look at the images of the graffiti over the past two years you can almost read the history of Egypt…as well as the sentiments of the street, or the sentiments of people who may not have access to media, or may feel betrayed by the media in the way the revolution is being portrayed or the opposition is being portrayed.

[Author note: Her memory was accurate. According to Unicef’s 2005-2010* statistics, the total adult literacy rate is 66%].

Why the “Women in Cairo” blog post? What prompted it?

Because there was nothing out there about female graffiti artists! And even though my photographs were not new, and the artists were not new—I’d written about them before in some my posts, I found that there was absolutely zero coverage or zero attention given to female graffiti artists. And I wrote this post at a time when, I think it was just before the anniversary of the revolution, or just after, and I was very upset about the increasing reports of sexual harassment and sexual violence against women in Tahrir and other parts of Cairo…in Egypt itself. And because I empathized and felt so strongly about it somehow that got me to thinking about all of these amazing women that I've met and read about and why aren’t they getting any credit? I know that it must be twice as hard to be a woman in a man’s world, and Egypt is a very patriarchal society, and as a blogger observing them in action, observing them working in the street, I’m very aware of the street atmosphere and the public sentiment toward women working versus toward men. Most of these women would work in groups, or work alongside, and some would work alone. It would definitely be riskier, I assume, for women to be working alone on the street in such a turbulent time, in such a violent atmosphere. If you’re working through protests, or during riots, and on a wall in a public street where people can attack you simply in broad daylight and no one will do anything. That’s a huge risk to take for art.

Is there a common message, image, or theme that you see amongst the street art painted by women?

I don’t see a common message, image, or theme among street art painted by women. The point that I was trying to make in my blog post was that their gender doesn’t influence their work as much as their presence on the street or whatever is happening on the street. And I think the work that they’ve made should be held on the same level of recognition as that of their male contemporaries. Not because they are women. This is a trap that Egyptian women tend to fall into when typecast by Western media, or by being depicted by pro-feminist supporters in the sense of—oh look she’s a woman so let’s appreciate her art. No. If you took the woman away and I showed you the art, and you wouldn’t know if it was a man or a woman, you would still be able to appreciate its aesthetic value and its message. If you look at Hanaa El Degham’s Tower of Misery, you see these faces of poor Egyptian peasants carrying gas cylinders on their backs and their heads, and it’s almost like a pyramid. And at the top of the pyramid you see the eagle, or the ancient Pharaohnic symbol of the eagles that represents the Egyptian flag. Man or woman could have made this. You don’t see anything of her gender influencing the art that she’s created. These artists are equal to men in talent. The point I was trying to make is that they have to suffer double in order to make this art because of the risk of them being on the street, and also because you are in a patriarchal society, and also because of the competition from their male peers. Now they’ve been fully supported and appreciated by male artists, I don’t want to say that they’ve been criticizes or harassed or oppressed by anyone.

In your early blog posts, you located the influences, references, and aesthetics of Cairo’s street art scene as saturated in Western pop culture (which you also noted limits public consumption and reception). It seems to me that the usage of Western pop cultural references and such might actually further the misrepresentations of women as oppressed, lacking liberation, or as you say “living in caves making mud paintings.” Are you seeing the same kinds of influences in what the women are painting?

It was a reference to the Western perception, the perception of Western media, Western society of Egyptian women as oppressed. Just to clarify that it wasn’t about graffiti. I really don’t see Western influences in what these women are painting. I believe that they all have their distinctive different styles. If you look at Aya Tarek, she comes from a family of artists. In fact her grandfather would make posters and large-scale illustrations. Her art, if you’d have to put a label to it, it would be maybe more Western than it is Egyptian, but still it is very distinct and unique. Hend Kheera would use stencils and posters and sometimes shed make pop-cultural references would be understood by a Western audience, but also by an Egyptian audience.

You seem to have quite a few comments on each entry—what are your thoughts on how the public is responding to your blog?

I don’t actually know how the public is responding to my blog. I’m continuously surprised when I meet people who read my blog, because it did start out as a hobby. And I did not think that other people would read it aside from my friends and my family. I still, two years later, cannot believe that it has reached the number of people that it has across the world. So, whenever I get an email from someone saying we want to ask you questions, or we read your blog, or we like it, or I meet someone that I really respect—a journalist or an academic —and they say they know about me and my blog I’m seriously surprised. I suppose that even though it is a very niche market blog, very specific only about graffiti, but because all my content is about graffiti it is very easy to find on Google. It’s in English, which means it’s read by a mostly English-speaking audience so it’s not necessarily targeting an Egyptian audience. But its good in the sense that I feel like I may have contributed.